Having lost only a shoe and a not-particularly-important organ, Mr. Korda trudges through a cornfield, surrounded by the wreckage of his airplane. A minute ago, he had appeared before God’s judgment, where his sinful soul was to be repaid according to its deeds — but he decided on his own that it was too early to tally up his vices, and once again brushed death aside like a speck of dust on the lapel of an expensive jacket.

And Anatol Korda had amassed more than enough sins — especially if you include in the list the use of slave labor and the condemnation of an entire nation to starvation. But settling accounts with Heaven’s office in the afterlife is of no concern to the distinguished businessman for now, despite the fact that attempts on his life have long since become part of his daily routine.

Having once again slipped away from the other side, Mr. Korda decides to bring to life the project of his lifetime. To do so, he seeks out his long-estranged daughter, who — for the sake of irony — has become a Catholic nun, and places upon her the burden of inheriting all his wealth. In response, the young woman offers her father a probationary period, during which he must prove his worth as a parent and show a willingness to correct at least a pinch of his mistakes.

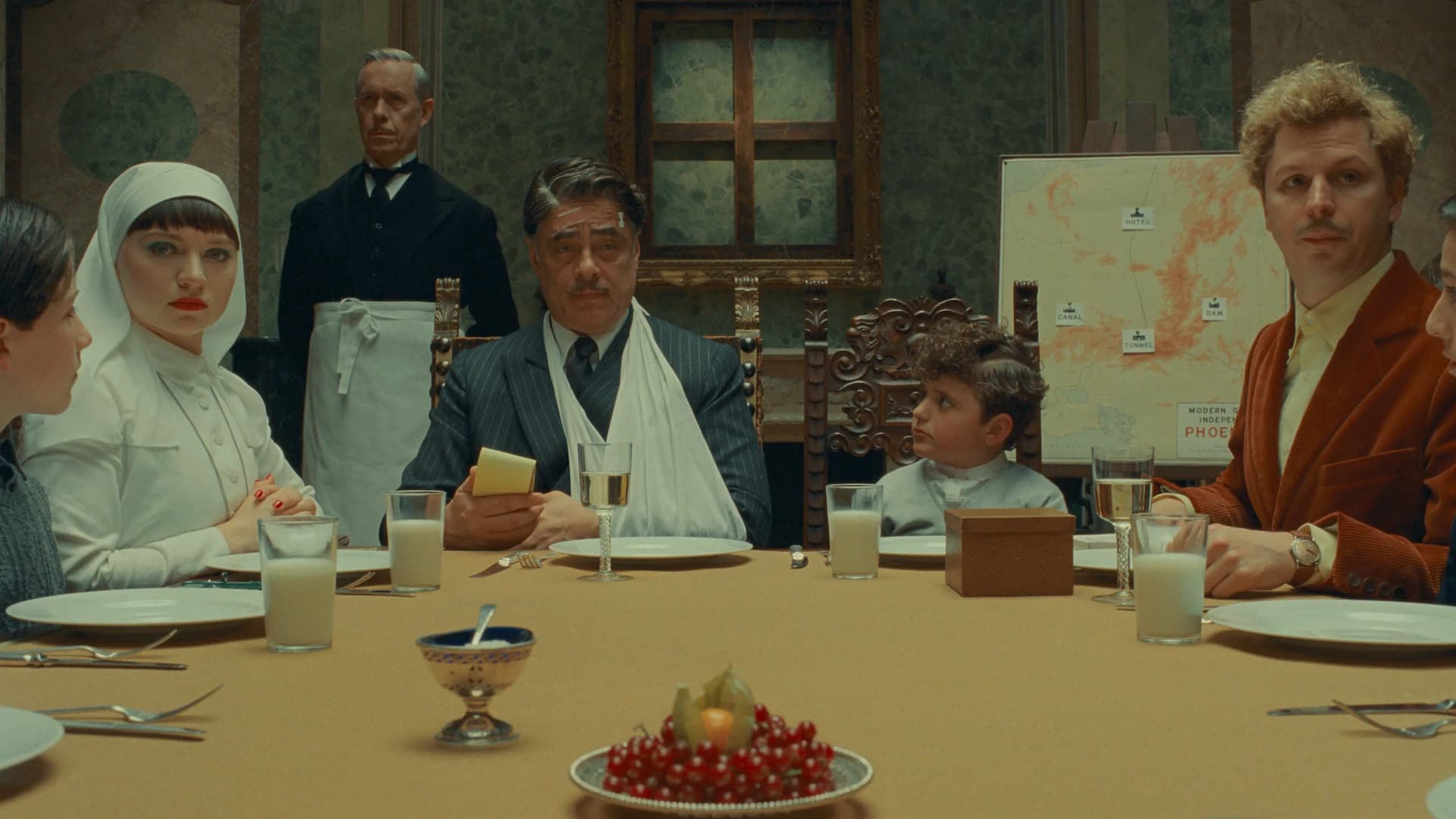

“The Phoenician Scheme” project is full of elaborate maneuvers and cunning tricks, as well as barely legal deals with gangsters, kings, and even Anatol’s own relatives — not to mention constant spying on rivals and entire governments. The ultimate profit and the plan itself are impossible to decipher, which is why only a slick businessman like Korda can convince a motley array of sponsors of his inevitable success.

Wes Anderson’s new film is the familiar medley of absurdity, modernism, and biblical moralizing — this time wrapped in a spy action flick. The director doesn’t even attempt to keep a straight face, and his creation seems on the verge of falling apart, revealing all its hidden madness at once. The ears of creative eclecticism stick out from beneath the coat of a simple story — but that’s the whole point.

A journey through a Phoenicia torn apart by gangsters, communists, and the armies of various kings leads to the spiritual transformation of the main character — from a cold-blooded magnate into a responsible father. The daughter, in turn, adopts some of his traits, gradually bringing the unlucky family closer together. And not even the periodic assassination attempts — after which Korda briefly visits the heavenly court — can tear them apart.

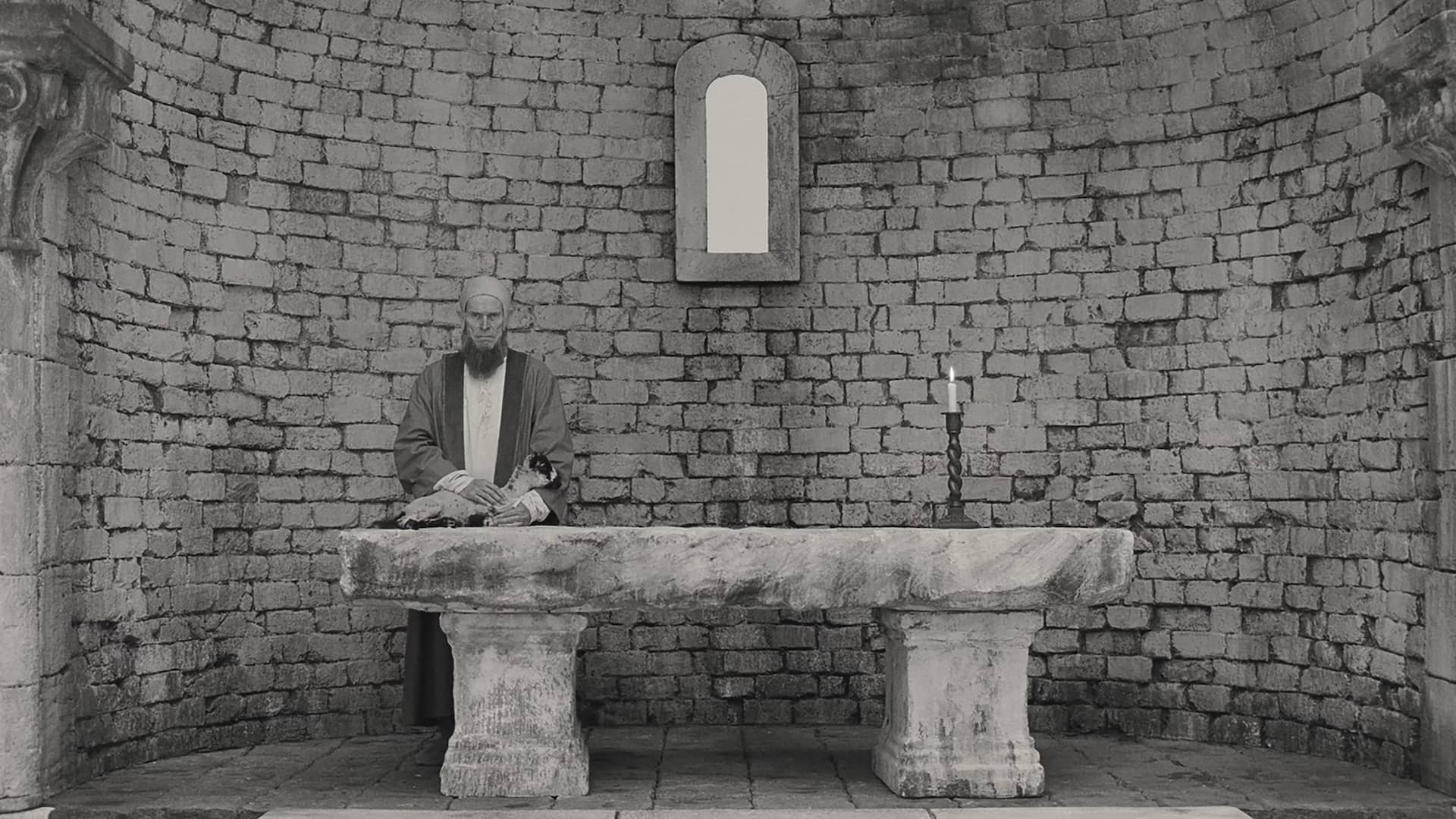

With each death, Anatol passes through new departments of the heavenly apparatus and draws closer to the answers he needs. The black-and-white scenes in Heaven’s office are more than just a joke about divine bureaucracy. Wes Anderson, perhaps for the first time, is so straightforward in his desire to start an adult conversation about the redemption of sins — almost without clowning and his usual irony.

Layered over the biblical drama is a map of “modern Phoenicia”, whimsically reimagined as a fairy tale of kings and bandits. This East — sweet as the treats in a confectioner’s shop, yet torn apart by comical tyrants — exposes imperialism and greed. But a split second before the story risks becoming too serious, it once again slips into outright farce.

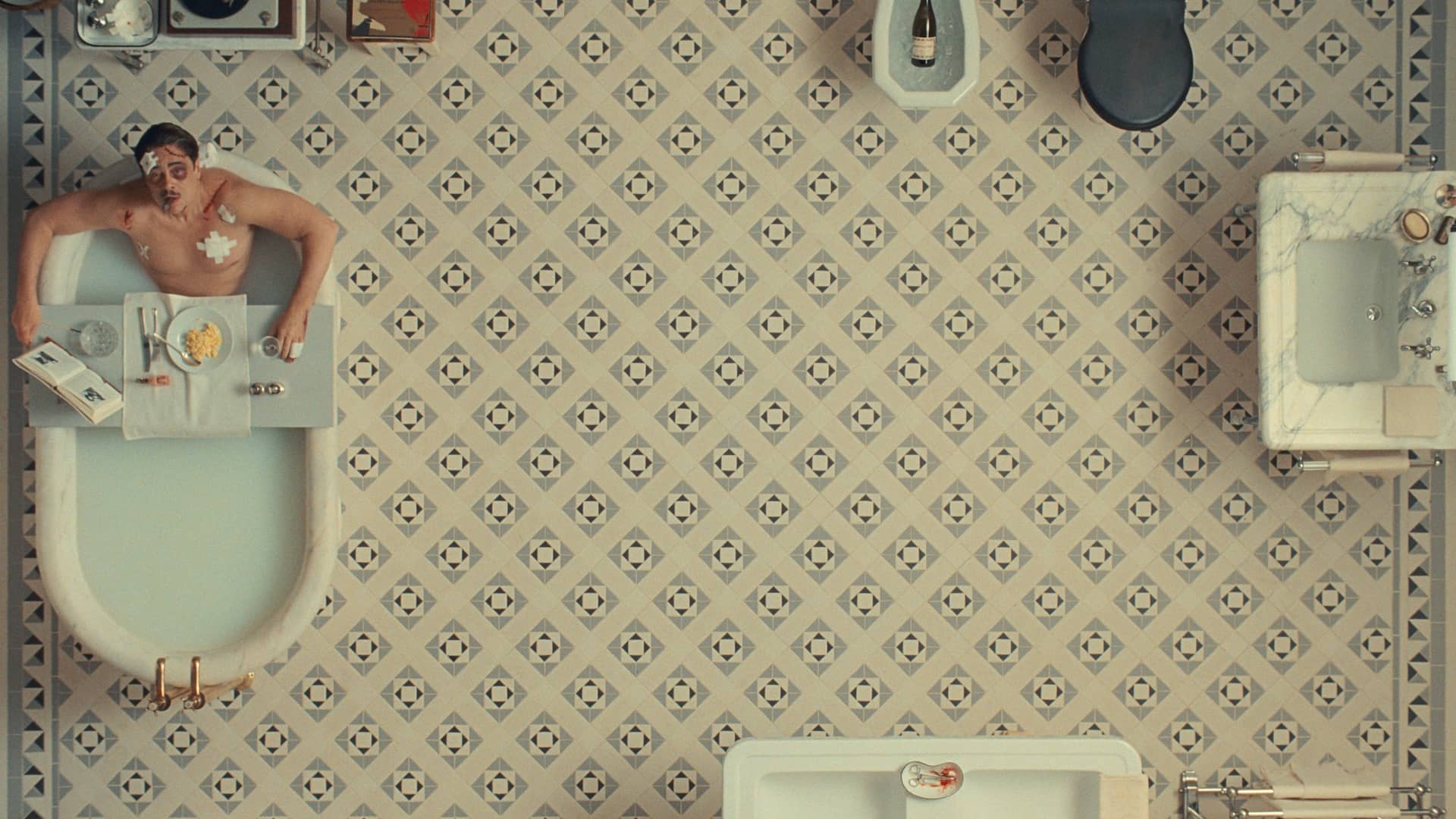

Wes Anderson assembles his “Eastern bazaar” from pastel Art Nouveau, colonial-capitalist parodies, and symmetrical geometry. The frames resemble both vintage posters and accounting spreadsheets at the same time. Straight lines, watercolor tones, and neatly “shelved” characters weave together into a familiar score.

The symmetry lies not only in the centered mise-en-scène but also in the very editing style, which relies on deliberate repetitions, synchronized dialogues, and rhymes. Whenever the main character kicks the bucket yet again, the film shifts into the strict black-and-white blocks of the “Heavenly Office” — a detached gaze, head-on frontal framing, and an almost Bergman-like severity.

In this world, even the words echo each other. Stern enumerations, reverence for time, and polished phrases form a metronome that, set in motion from the very first second, dutifully keeps the beat. In the noisy ensemble of negotiations, presentations, and formal visits, it is this rhythm that holds the chaos of spy intrigues in check. The style quite literally structures the story, keeping it from falling apart into a mere collection of sketches.

The geometry of the frame seduces with a sense of control, and symmetry promises justice and order. But in the end, harmony is built not on equal shares and percentages, but on commitments accepted. Korda’s fatherhood becomes the break in the frame’s perfect ornament — a reminder that the world cannot be made perfectly balanced, but one can at least try to find peace with oneself.

“The Phoenician Scheme” insists that the redemption of sins is no miracle, but painstaking work — and only the “director” himself can change the angle. Life, too, is no bright and polished shop window. It is more like a cluttered workshop, where the only chance for success lies in the labor of self-improvement — patient and awkward, like the first draft of the next life.